It's a quiet morning in San Francisco, with soft sunlight illuminating patches of thick fog billowing over the Golden Gate Bridge. A solitary unmanned aircraft—a 4-pound, battery-powered wedge of impact-resistant foam with a 54-inch wingspan, a single pusher-propeller in the rear, and a GoPro video camera attached to its body—quietly approaches the landmark.

Raphael "Trappy" Pirker controls the aircraft from a nearby hill. The bridge is within sight, but the 29-year-old enjoys the scenery through virtual-reality goggles strapped to his head. The drone's-eye view is broadcast to the goggles, giving Pirker a streaming image of the bridge that grows larger as he guides the radio-controlled aircraft closer.

Pirker, a multilingual Austrian and a master's student at the University of Zurich, is a cofounder of a group of radio-control-aircraft enthusiasts and parts salesmen called Team BlackSheep. This California flight is the last stop of the international group's U.S. tour. Highlights included flights over the Hoover Dam, in Monument Valley, down the Las Vegas Strip, and through the Grand Canyon. The team has also flown above Rio de Janeiro, Amsterdam, Bangkok, Berlin, London, and Istanbul.

The Golden Gate Bridge now fills the view inside Pirker's goggles. He's not a licensed pilot, but his command over the radio-controlled (RC) aircraft is truly impressive. The drone climbs to the top of the bridge, zips through gaps in the towers, dives toward the water, and cruises along the underside of the bridge deck. Months later, the self-described RC Daredevils post the footage on YouTube, where nearly 60,000 viewers watch it.

Team BlackSheep is willfully—gleefully, really—flying through loopholes in the regulation of American airspace. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) allows unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to fly as long as their operators keep them in sight, fly below 400 feet, and avoid populated areas and airports.

The FAA also forbids any drone to be flown for business purposes. "In the U.S. right now, it's completely open, so long as you do it for noncommercial purposes," Pirker says. "The cool thing is that this is still relatively new. None of the laws are specifically written against or for what we do."

While the FAA did not sanction Team BlackSheep for buzzing landmarks as a publicity stunt, it has shut down other for-profit drone operators, including Minneapolis-based Fly Boys Aerial Cinematography, which was using drones to take photographs for real estate developers. are specifically written against or for what we do."

Even the military and other government operators must obtain FAA waivers to operate drones. That means that flying over a wooded area is fine for an amateur, but a fire department that uses a drone to scout a forest fire in the same area requires special federal permission.are specifically written against or for what we do."

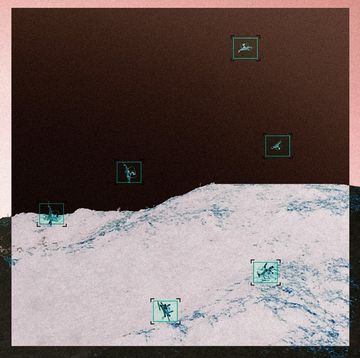

Federal, state, and local agencies can apply for FAA waivers to be able to put drones to work. Although the process is cumbersome and time-consuming, there has been a sharp rise in requests (see "Rising Drone Demand," page 81). For example, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) operates a fleet of 21 T-Hawks, ducted-fan UAS that can be readied for takeoff in 10 minutes and can ascend to altitudes of 8000 feet. The USGS has obtained permission to use these craft to view hard-to-reach cliff art, track wildlife, inspect dams, and fight forest fires. Others are not so lucky. Last year the FAA grounded a $75,000 drone that the state of Hawaii bought to conduct aerial surveillance over Honolulu Harbor. The agency would not waive the rules because the flights were too close to Honolulu International Airport.

In a bid to force a reassessment of the regulations, Congress in 2012 ordered the FAA to open the National Airspace System (NAS) to unmanned aircraft. The law sets a deadline of 2015 for the FAA to create regulations and technical requirements that will integrate drones into the NAS. "Once the rules of the air are established, you're going to see this market really take off," predicts Ben Gielow, a lobbyist for the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

The FAA predicts that, because of the law's passage, 30,000 public and private flying robots will be soaring in the national airspace by 2030. For a sense of scale, 350,000 aircraft are currently registered with the FAA, and 50,000 fly over America every day.

Some experts express alarm at the prospect of tens of thousands of extra aircraft flying in the already cramped U.S. airspace. "To most of us air traffic controllers, it's unimaginable. But we're also smart enough to know it's coming," says Chris Stephenson, an operations coordinator with the National Air Traffic Controllers Association. "I refer to UAS as the tsunami that's headed for the front porch."

Police Robots Wait for Takeoff

On May 9, 2013, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, were frantically searching for a missing person at the scene of a car accident. They knew the 25-year-old man was out there—the dazed victim had walked away from the scene in just a T-shirt and pants, calling for help on his cellular phone before falling unconscious into the snow.

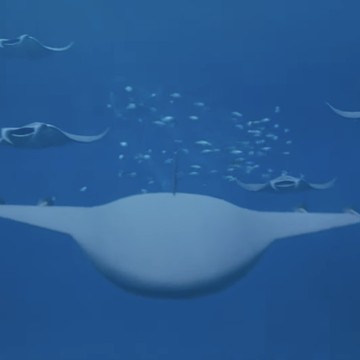

Stymied, the Mounties called forensic collision technician Cpl. Doug Green and his partner—the Draganflyer X4-ES, a 36-inch-wide quadrotor drone equipped with an infrared camera. Canada, which has been working out detailed regulations for commercial use of UAS since 2008, allows police to operate drones, thus setting the stage for what the Mounties say was the first life-saving rescue by a civilian drone.

Green commanded the small quadrotor aircraft into the air and directed it across the snowy landscape. The forward-looking infrared cameras quickly saw the warmth of the victim's body, 2 miles from the accident scene, and the Mounties moved in to rescue him.

Despite such potential to save lives, government drones can become tools of overreaching law enforcement.

In June the citizens of Iowa City, Iowa, collected thousands of signatures on a petition that successfully pressed the city council to ban license-plate readers and drones. The fact that neither was operating in Iowa City was no matter. The effort is part of a larger trend. This year at least three bills to restrict the use of UAS in collecting data or conducting surveillance without a warrant have been introduced in Congress, and laws that sharply curb the police use of drones have either passed or have been proposed in 14 state legislatures.

The same things that make drones useful cause the public to worry: UAS are much cheaper to own and operate than helicopters or fixed-wing airplanes. "Drones drive down the cost of surveillance considerably," Ryan Calo, an assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Law, testified before Congress in March 2013. "We worry that the incidence of surveillance will go up."

The International Association of Chiefs of Police last year adopted guidelines stating that law enforcement agencies should obtain search warrants before launching UAS to collect evidence of a specific crime and must delete all unused images.

These steps may not be enough to mollify critics. "Just because the government may comply with the Constitution does not mean they should be able to constantly surveil, like Big Brother," Republican Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa said at the March congressional hearing.

>

Rise of the Mom-and-Pop Drones >>>

Rise of the Mom-and-Pop Drones

David Quiñones takes a homemade quadcopter out of the trunk of his black SUV. The 38-year-old sole proprietor of video production company SkyCamUsa attached a video camera to a swiveling servo and duct-taped it to the quadcopter's fuselage. He carefully lays his drone on the ground of the small parking lot outside the Kissena Velodrome, a cycling track in the New York City borough of Queens.

For six years Quiñones has been "suffering and waiting" for FAA approval to offer his homemade fleet to advertising, television, and movie productions. His time has nearly come: Next year the FAA will issue rules allowing electric-powered UAS that weigh 25 to 55 pounds for commercial flights. When that happens, "it'll open up a whole new world of possibilities," Quiñones says.

Better controls, longer ranges, and miniature, high-resolution cameras have revitalized the radio-control-aircraft community. Some of the cornerstone technologies of military drones, such as automatic camera stabilization, the ability to follow waypoints of a flight path, and the automatic process to return home if controls are lost, are now available to RC hobbyists. Many of these amateurs will be trying to turn pro next year.

The FAA rules will accommodate their ambitions, but the agency will also impose restrictions. The FAA is not providing many details, but its regulations will certainly limit when a drone can fly and likely will require licensing of the aircraft and the pilots. Even Team BlackSheep's Pirker argues that there should be a way to distinguish capable RC fliers from amateurs. "There needs to be some kind of process that evaluates if you know what you're doing, something in the line of aircraft or pilot certification," he says.

The impact of the FAA's new regulations is expected to be dramatic. Agency officials estimate that 7500 small commercial UAS will be operating in U.S. skies by 2018.

High-Altitude Blues

There's a hurricane forming in the Atlantic Ocean, gathering strength off the coast of Africa. It's time for NASA's Global Hawk to go to work.

Hundreds of miles from the storm, pilots on the ground in Wallops Island, Va., level the 44-foot-long drone at 60,000 feet, aiming it over the top of the hurricane. This altitude is twice as high as the maximum at which manned hurricane chasers operate. From that unique vantage, the Global Hawk aims Doppler radar, radiometers, and microwave sensors into the heart of the storm.

Whereas manned planes usually have to return to base soon after they reach a hurricane developing in the distant Atlantic, the Global Hawk can linger on location for dozens of hours, collecting data that can be used to predict the system's path and severity. NASA last year flew one Global Hawk per storm; this year two UAS will study each hurricane from different vantage points.

From the volcanic plumes of Costa Rica to the icy north Atlantic, drones go where sensible pilots cannot or will not go. The larger and more powerful the aircraft, the more payload it can carry and the farther it can travel. And drones with gas-powered engines can stay aloft longer than their smaller, battery-powered brethren or similar- size manned aircraft.

Oil company engineers planning the least environmentally risky route of a new pipeline, for example, would not be interested in a radio-controlled T-Hawk. They'd want a fixed-wing aircraft the size of a Cessna to efficiently scan the terrain below in a single flight using 3D-radar-mapping sensors.

Congress is demanding that the FAA develop a plan to govern larger unmanned aircraft by September 2015. In theory, everywhere we today see a helicopter or private airplane, there could be a drone. Future operators of FAA-certified unmanned aircraft could simply file a flight plan before takeoff, as pilots of manned aircraft do. But the FAA's rules will likely include prohibitive technical regulations.

Coming up with safety standards for large drones that fly at thousands of feet is far more complicated than regulating the operation of an RC plane zipping along within the operator's line of sight. The current standards for manned aircraft require pilots to "see and avoid other aircraft." Without humans on board, flying robots will need to think for themselves to avoid other airplanes.

Aerospace companies and the Pentagon are developing systems that combine radar, cameras, or other sensors with software that will detect aircraft and change course to avoid them. Some of the systems rely on ground stations, while more advanced versions are incorporated into the drones.

This solution comes with engineering drawbacks, however. "By hanging that type of technology on an unmanned aircraft, you start adding a lot of weight and draining a lot of power," says Viva Austin, the civilian official in charge of the Army's ground-based sense-and-avoid project.

John Walker, a former FAA director and cochair of a federal advisory panel that is developing standards for UAS technology, says technical demands will likely slow the pace of drone adoption. For example, the panel may recommend that the FAA require sense-and-avoid systems that will steer a drone away from potential collision courses, not just perform the simple "climb or descend" instructions current systems give a pilot.

That requires a flight-control computer powerful enough to handle complex algorithms. "What we're talking about for separation assurance is climb, descend, turn left, turn right," Walker says. "It's going to take a tremendous amount of modeling and simulation."

The result? Walker predicts manufacturers and operators will have to invest a lot of money and years of work to meet the pending FAA requirements. Once the tech is developed, the feds will test and certify it, causing more delays. What the coming drone invasion will look like is still uncertain. Even the FAA is unwilling to predict how the regulations will shape the future of flight. In a written response to Popular Mechanics' questions, the FAA said that "until the plan is complete, the exact extent of UAS operations proposed for 2015 is difficult to predict."

Despite the assured language of the law, the integration of UAS into America's airspace can't be done with the stroke of a pen. That might be seen as a good thing by those who are nervous about the coming wave of unmanned aircraft. But one day the technology and the laws will be ready and the skies will be fully open to robots. How they are used will be up to us.

Additional reporting by Glenn Derene

>