No one needs this motorcycle. And, more to the point, the person who would buy the 2015 Ducati 1299 Panigale S is a rider who needs it least. I'm thinking of Justin Bieber, famed for his lack of good judgement while operating vehicles, who was seen riding a Ducati 848 Evo a few years ago wearing no protective gear and with his feet placed incorrectly on the pegs while riding illegally in the breakdown lane. If you're rich, hubristic, and wake up one morning thinking, "I want to buy a stupidly fast street-legal motorcycle," chances are you'll end up at a Ducati dealership (or, arguably, BMW or Kawasaki) signing paperwork for this bike.

Thing is, after living with a brand new $25,000 1299 Panigale S for ten days and putting over 1,000 miles on the odometer (thank you, Ducati Triumph New York, for being cool about that), I can't say that I wouldn't do the same. This bike is a tool built beyond the capabilities of all but a tiny minority in the world. But we don't always buy things for who we are. Sometimes we buy things for who we think we can be.

Speed

"How fast?" That's the question from every friend and at every gas station. Motorcycle companies like Ducati don't publish top speeds or zero-to-60 times, so to answer that question, here are some numbers. The motor produces 205 horsepower, which is more brawn than some four-wheel hatchbacks. But where an economy car is laden with airbags and sheetmetal, the Ducati weighs just 420 pounds with a full tank of gas (not counting the rider). Simply put, with that power-to-weight ratio, no mortal would ever dismount this thing and complain that it wasn't fast enough.

Of course, numbers don't sufficiently illustrate the sensation of being on this thing when you take the leash off of its 205 horsepower engine. The feeling of that power is, after all, the reason idiots like me take enormous risks to come into contact with a motorcycle of this caliber.

I wanted to see if I could even glimpse this bike's limit, and an opportunity came on the Westside Highway in Manhattan. I was at the front of the line at a red light, and watched as some sadistic god of speed sent every car in sight off the road onto an exit ramp, leaving four lanes open. The green light dropped, and I opened up, moving forward through air at a speed that I think only pilots taking off from aircraft carriers can experience. Your brain ignores input from most of your senses, and this adrenal euphoria begins. I envy the people who apparently get this sensation from running marathons. So much cheaper, and less likely to kill you.

In first gear, hitting 10,000 rpm, I smoothly kicked the shifter up into second—no clutch necessary as the bike helps blip the throttle to match revs. Then I went a little faster, only once looking down after hitting third gear as the color dash showed the number 90 turn into 91 mph. I kept my knees tight on the gas tank to keep the bike from leaving me behind. With wheelie control turned off, the bike feels lighter as the torque gives a middle finger to physics and the front tire briefly hovers inches above the asphalt.

Around what must've been past the 100-mph mark, two movie cliches happened. Even with my visor down, my peripheral vision became runny, like a watercolor of the barriers and medians on each side. It was like the tunnel vision accompanied by white noise that you see in every war movie since Saving Private Ryan. You get superhuman focus on your movement as you float through space. A few milliseconds into this, I processed the tail lights of the stopped pickup truck ahead.

I grabbed the right lever in panic, braking as urgently as I could while picturing my body's trajectory, thinking how I'd phrase the call to Ducati that I'd trashed one of their $25,000 bikes. But I came to a halt in time, with both wheels on the ground. The anti-locking brake system (it's too sophisticated to just call ABS) didn't even kick in, and I came to rest at a polite distance from the beater Toyota in front of me. I checked the my rear-view mirrors for red and blue lights, put the bike in neutral, and put my legs down.

Then came the second cliché. I started dry-heaving, thinking in slow motion about how I'd clean vomit from my helmet liner. But that moment passed, and I kept the bile inside my stomach. Phew. Nothing makes you so certain that you're about to meet your thrilling doom as riding a bike fast on a public road.

Idiot-proof?

Most riders I told about the bike said the same thing: "That's dangerous. I want nothing to do with it." I felt the same thing, terrified of embarrassing myself as I pulled away from the dealership. I even asked Marcos, the shop's Panigale expert, to keep the bike in Wet mode, a combination of traction control and power reduction that'll keep you from extracting too much of the bike's power.

Within a few hours, though, this devil in your head tells you to have a little fun. So you hold down the blinker-cancel button, turn wheelie control to OFF, and go into Race mode. Thankfully, Ducati packed the Panigale with a swath of computers dedicated to keeping the rubber side down in spite of the riders like me who overestimate their ability to handle this much motorcycle.

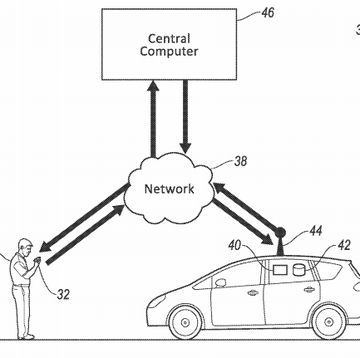

As you approach a tight corner, applying the front brakes and beginning to steer towards the apex, the Ducati's army of sensors feed measurements to a central processor. The bike slows down and the weight goes forward while the front forks (the tubes that connect the front wheel to the bike) stiffen, keeping the bike balanced throughout the turn. It'll permit just enough compression to flatten the front tire, giving the rubber a large contact patch against the asphalt for control during the turn, then stiffen to keep weight distributed between the front and rear wheels. Meanwhile, another sensor calculates how far the bike is leaning from upright, informing the steering and suspension to keep the bike upright and moving.

In practice, riding through curves on the App Gap in Vermont, the result was either real or imagined unshakable stability, like the wheels were set in roller coaster tracks. After approaching the turn with slightly more speed than was comfortable, I spotted the exit, turning my right wrist to accelerate towards the straightaway that opened up ahead. The rear suspension stiffened to counteract the power being sent through the rear wheel. The bike leveled out, both tires still planted, as it shot forward like a rock from David's sling.

Riding it, you feel a confidence inspired by having the world's most sophisticated two-wheel technology guiding you. During maneuvers where I'd normally fear an expensive low-side crash, I'm instead strangely comfortable, thinking, "Well. If I'm going to attack this turn, I have the most precise tool I'll likely ever use." You start to trust in the bike, and it rewards your faith by putting stupid grins on your face.

Ducati's idea of practicality

If it weren't obvious, there's no such thing as relaxation or comfort on this bike. Granted, the ride I took—from a hot New York City parking garage to the green two-lane roads of Vermont—probably wasn't how the bike's architects intended the Panigale to be used. But through those highways and verdant two-lane backroads, the bike was merciful, even civilized. Ride-by-wire throttle — meaning, when you turn the right grip, a computer is sensing how much you're moving it, and opening the engine accordingly, rather than you moving a cable yourself — smoothed out my jerky acceleration while passing trucks. The stock seat is more comfortable than most bikes I've owned. Even if you're not in a race tuck, you can ride for a while before anything hurts.

But three hours in to a eight-hour ride, the Panigale started beating up my legs and spine. The insides of my glutes burned so badly I wanted to sit in an ice bath, and even at 90 mph on the highway, I could feel and hear my knees pop when I extended them. Particularly in traffic, the exhaust pipe running underneath the seat would occasionally feel so hot that I worried that my leather pants had fused to my hamstrings. I regretted not buying more comfortable pants.

But no one buys this bike for a road trip. For the couple of hours before my legs and back started complaining, you understand that the ergonomics here are there to enable you to cut through air as fast as possible.

After the novelty

Thinking about what it would be like to own a 1299 Panigale S, I had to shake off outdated prejudices about Italian bikes. Through the 90s, Ducatis were maligned for frequent breakdowns and short service intervals. But the Panigale, with all its precision engineering and moving parts, requires little maintenance. Change the oil and filter at about 600 miles and you're free to continue thrashing the bike until the odometer hits 7,500. A Japanese-tough Suzuki V-Strom, by contrast, needs attention 1,500 miles earlier.

It's strange to have that reliability on this type of bike because every component on the Panigale is as expensive, sophisticated, and often complicated as you can buy. The magic suspension is made by a Swedish company called Ohlins — a requisite on any superbike. The exhaust is from Akropovič, the Slovenian manufacturer responsible for making the bike sound like a lion that's been kicked awake. (Unlike the near-monotone hiss you hear from Japanese super bikes that go by on the highway, the Ducati is a baritone that gets more feral above 5,000 rpm). Then, there are all the electronics and wiring making it all work in harmony.

The brakes, in particular, are a huge part of what makes a motorcycle this overpowered capable of being used in a civilized manner. The Panigale's front wheel has two Brembo discs controlled with four-piston calipers. Grab a fistful of the right lever as I did, and in otherwise lethal conditions, you live .

On the day I had to return the bike, I understood why someone would buy this thing. You want to keep getting back on it because you feel like a student getting a lesson from a tennis instructor who's hitting at half-speed. In normal riding, you don't really have to go above third gear, but I wanted to get to a speed that required fourth. That pursuit can bring out a bit of zen when riding serious roads. Again, I wish I got that from jogging.

Whether or not that sensation is worth $25,000 isn't a rational question, but there are some facts to consider. That money buys you a tool that'll take you to the limits of your capabilities, but with a safety net to catch you if you fly too close to the sun.

As Editor in Chief, Alexander oversees all of Popular Mechanics’ editorial coverage across digital, print, and video. He has been a science and technology journalist for over 10 years and holds a Master of Arts degree from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He was previously Technology Editor for Popular Mechanics and before that, a contributor to publications including the Wall Street Journal, Wired, Outside, and was a product tester and reviewer for The Wirecutter. He has been called on to appear on live and taped broadcast programs including Today and programs on MSNBC. He lives in Pennsylvania and rides a 2012 Triumph Street Triple R motorcycle.